Faculty, students, and staff at Bucknell, Bloomsburg, and other institutions in Central Pennsylvania have started a community action research group focused on our version of Urban Institute’s Community Platform. As part of our group work we recognize that we need to work our way through the community studies literature and to that end we want to post reading summaries in some accessible place. For now this blog is it.

What follows is a short note I included in an email to Bucknell colleague Jordi Comas about Xavier de Sousa Briggs’ book DEMOCRACY AS PROBLEM SOLVING. Jordi and I plan to work ourselves through several books including WHY THE GARDEN CLUB COULD NOT SAVE YOUNGSTOWN, so this note says a bit about the two books. The Briggs book was recommended by Tom Pollak, creator of the Community Platform system at Urban Institute. Tom’s primary value is to build leadership and civic capacity at the local level. Although the Community Platform is a wonderful technical tool, his vision is that it can be a means of building collaboration and civic capacity. That certainly is our orientation here in Central PA.

So here are my short comments on Briggs (based on reading 2/3 of the book)

I’m about 2/3 throug Briggs. I returned my copy to the library so you can get it there. It’s very similar in theme and focus to Youngstown except that it has multiple case studies and it’s international. It would be very interesting to compare the perspectives on civic capacity in the two books. The Youngstown book is much more built around the notion that communities have interorganizational networks of nonprofits that are more or less dense, active, and inclined to come to the fore to deal with civic betterment. Briggs picks some cases (most notably Pittsburgh) that are famous for interorganizational connectedness and civic mobilization and while he thinks they are good examples of civic mobilization he also shows quite convincingly that in Pittsburgh the reputation is a myth to a significant extent.

I was pushed to look at Briggs by Tom Pollak who wants to believe that the Community Platform is an instrument fostering the development of civic capacity. Pollak views this as social action and not as a mechanical product of his tool, the community portal or platform. Briggs thinks civic capacity is real and important but he thinks also that it is chaotic and that social science theories like political pluralism imagine a level of order and directional social progress that is a fantasy. The chaos element appeals to me but it also leaves me puzzled about what to DO. The YOUNGSTOWN book is much more programmatic about what to do—build and nurture the background interorganizational network. That’s what I’m trying to do via the platform and the notion that there’s variability in network density and network capacity between communities suggests that some sort of “health practices” approach might help. Counter to this is Putnam’s notion that civic capacity is historical and deeply rooted in local traditions so it is not easily altered.

This blog presents a report on the impact of Ethiopia’s civil society organizations and indigenous people who do NGO research and lead these organizations. Because I have family members and friends who live in or have fled Ethiopia, over the last three years I have heard many stories about arrests, intimidations, and organizational closings. These actions have cut off what had been a fifteen year tradition of building civil society organizations and using them to address desperate poverty and to build democracy in this country. Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa with about 90 million people. It occupies a land area one-third the size of the United States. It also is one of the poorest countries and food insecurity is a chronic problem there.

I spent two weeks in Ethiopia during April 2010 and most of my time was occupied interviewing NGO leaders and visiting development projects in the countryside. I presented myself in these interviews as a board member of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organization and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA). As a board member I think we ought to support the principle that citizens all over the world should have basic rights to freedom of speech and association.

Furthermore, within the framework of certain principles of operation, nonprofit organizations (as we call them in the United States) should be protected from governmental interference and that their leaders should have due process protections. I have worked with the Italian Active Citizens Network for several years and have been aware of their effort to create a standard legal code defining the rights of nonprofit organizations in all EU states (FONDACA, 2006). I do not believe that this code has been passed by the EU.

The FONDACA code, worked out in collaboration with similar citizens organizations from across Europe, began with the recognition that some countries in the EU have restrictive laws concerning what it calls “active citizenship organizations (ACO)” because their legal traditions have not recognized rights to free association. As with other domains of legal and economic life in Europe, the FONDACA group argued that a uniform code is needed. Basic principles are that ACOs should be treated as autonomous firms and as firms they should have their autonomy legally protected. Furthermore, ACO members should have their rights to associate freely and to engage in free speech on public issues where their actions are not politically partisan, violent, or dangerous.

My thought is that ARNOVA ought to endorse the FONDACA charter and support the principle that nonprofit and civil society organizations should be guaranteed certain freedoms. Furthermore, as an organization we should give expressions of concern when those rights are abused. We ought to reach out to national nonprofit associations in countries that are affected and we also should invite nonprofit scholars (some of whom I met in Ethiopia) to participate. We should communicate with international charities and governments that continue to provide aid and support in countries where civil society rights are abused. We also should, as researchers, teachers, and activists, teach about civil society principles and abuses that occur around the world.

My investigations in Ethiopia were meant to explore how a restrictive NGO law is implemented in practice. Do civil society organizations retain their rights as autonomous firms? Are rights defined and protected in terms of free association, free speech, and nonpartisan voter education and mobilization? If there is a problem my intention is to convince ARNOVA to pass policies that endorse political freedom for those involved in nonprofit organizations around the world.

The Charities and Societies Law

In January of 2009 the Ethiopian Parliament passed the Charities and Societies Proclamation and after a one-year grace period this legislation known as the CSO Law began to be fully enforced by a new organization referred to as the Agency. The law distinguishes between charities, organizations that generally fall into categories defined by U.S. law as 501(c)(3) organizations, and societies, which are member benefit organizations.

The Law further distinguishes between organizations based on their sources of funding. Those that receive 90% or more of their funds from Ethiopian citizens are called “local” organizations. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) based in Ethiopia but that receive more than 10% of their funding from international sources (including citizens living overseas who donate funds back to organizations in their homeland) are termed “resident” organizations. Organizations based outside of the country and funded outside are called “international” organizations. Religious organizations are not affected by the Law nor are international charities that are registered with the government nor community-level, indigenous savings societies called “edir” or “equb”.

The charitable purposes that define the category of charities are organizations that: (a) work to prevent or alleviate poverty or disaster; (b) seek advancement of the economy and social development and environmental protection or improvement; (c) advancement of animal welfare; (d) advancement of education; (e) advancement of health or the saving of lives; (f) the advancement of the arts, culture, heritage or science; (g) advancement of amateur sport and the welfare of youth; (h) relief of those in need by reason of age, disability, financial hardship, or other disadvantage; (i) advancement of capacity building on the basis of the country’s long-term development directions; (j) the advancement of human and democratic rights; (k) the promotion of equality of nations, nationalities, and that of gender and religion; (l) the promotion of the rights of the disabled and children’s rights; (m) the promotion of conflict resolution or reconciliation; (n) promotion of the efficiency of the justice and law enforcement services; and (o) any other purposes as may be prescribed by directives of the agency.

Advocacy

Among these, only local Ethiopian charities and societies (those receiving less than 10% of their resources from other countries) can work on activities that fall in categories (j) through (n).

These activities are considered “advocacy” activities. The rationale of this legislation is “to ensure that nongovernmental organizations are ‘Ethiopian in character’, not to cut their funding, said Agtakilti Gidey, deputy director general of the country’s Charities and Societies Agency.”

“’If you provide a huge amount of money in this area and that money comes from outside, their work will not be for eht government and the people, it will be for foreigners,’ he said in an interview in Addis Ababa on May 12.” (McLure, Jason 2010). “Ethiopian Rights Groups Forced to Reduce Work Before Elections.” Bloomberg News, Friday, May 14. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-14/ethiopian-rights-groups-forced-to-reduce-work-before-elections.html [accessed May 14, 2010].)

Advocacy activities are distinguished from development or capacity building activities, which continue to be allowed. Three important areas of advocacy that have been ended for resident organizations are nonpartisan voter education including the organization of public forums about public issues and the performance of government, conflict resolution work, especially involving sustained disputes between ethnic groups or between critical social movements and the state, and work fostering development of rights, including the rights of women, children, and the disabled.

There is face validity to the government’s argument that wealthy international NGOs should not be conceiving and funding programs that advance their Western values rather than Ethiopian values. Our respondents complained, however, that the programs their organizations ran were created by Ethiopians and sold to outside funders rather than being responses out outside funding opportunities. The programs worked because they were locally adapted to the community practices and cultural values that prevail in Ethiopian communities.

My informants argued that the government has no test to distinguish an “Ethiopian” value from a Western value in the context of a program that develops women’s rights or that seeks to mediate a land boundary dispute between two ethnic groups. Furthermore, the government did not develop its regulations based on specific complaints about programs. Rather, the government sought change because when citizens learn about basic rights they begin to become interested in public issues and start to exercise the rights of free speech and free association. These rights might be seen as Western values but the counter view expressed by Nobel Prize winning Economist Amartya Sen (1999) is that basic freedoms are universal human values and that they necessary for the creative and entrepreneurial action that is necessary for development to occur.

Restrictions

Since historically there has been no practice of fundraising for impersonal organizations or abstract causes the new regulation has abruptly ended the activities of many important and effective civil society organizations. By one estimate the number of CSOs has been reduced form about 4600 to about 1400 in a period of three months in early 2010. Staff members have been reduced by 90% or more among many of those organizations that survive according to my informants (McLure 2010).

The CSO Law includes a variety of administrative controls that are to be administered by the Charities and Societies Agency. The implication is that NGOs are an extension of the state rather than private, autonomous firms. Yet the organizations are expected to raise their own resources, make their own program choices, recruit volunteers on their own, and be accountable to outside funding sources.

Among the administrative controls included in the Law, organizations may not spend more than 30% of their annual budgets on administrative expenses. They are required to produce an annual report and an audited accounting report. While these fit with standards of good practice in U.S. nonprofits the difference is that in Ethiopia the government is mandated to scrutinize the records of nonprofits and violations can be met with large fines or even imprisonment. This kind of monitoring would be extremely difficult for government to carry out in the U.S. and thus these regulations are not likely to be systematically enforced. Rather, the administrative controls give government the right to use these regulations to attack organizations they dislike. Furthermore, representatives of the Agency have the right to attend administrative meetings and to mandate changes in procedure based on the judgment of the representative. There is no mechanism for appeal. Nor do procedures guaranteeing due process exist for agencies to depend upon.

One respondent pointed out that he is personally held accountable to funders for the operations of his agency. Since his organization periodically undertakes large construction projects that require a year or more of planning he simply cannot meet the requirement that less than 30% of resources be spent on administrative expenses. His funder holds him to tight standards of accountability. Adherence to these controls could become impossible for him if agency representatives were to impose administrative changes that may or may not take his operating requirements into account. This individual also has encountered repeated demands for bribes and without a powerful funder behind him is sure that he would have ended up in prison for resisting those demands. This individual chose to close his NGO rather than try to live with the constraints imposed by the law.

Political Coercion

As McLure and others note, many observers view the CSO Law as one part of a broad-based effort by the government to eliminate public discussion of issues, to destroy opposition political parties, and to remove decentralized associations and service providers in favor of an authoritarian, centralized, hierarchical state. Important testimony and analysis is provided by the UK-based NGO, Human Rights Watch that provided an analysis of the proposed law in 2008 (Human Rights Watch (Oct. 13, 2008). Analysis of Ethiopia’s Draft Civil Society Law. http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/10/13/analysis-ethiopia-s-draft-civil-society-law-0 [accessed May 12, 2010]). That report found many parallels between the Ethiopian law and one passed in Zimbabwe in 2006. The Zimbabwe law led to widespread international condemnation.

Human Rights Watch recently followed with a long and detailed report based on over 200 interviews throughout the country. This spring 2010 report documents political abuses, restrictions of freedom, and systematic elimination of the social structure that supports civil society (Human Rights Watch (March 24, 2010), One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure. Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Ethiopia. http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/03/24/one-hundred-ways-putting-pressure [accessed May 12, 2010]). Another recent, powerful analysis, based on first-person observations and interviews, is provided by Helen Epstein in the May 13, 2010, issue of The New York

Review of Books Epstein, Helen (2010) “Cruel Ethiopia.” May 13. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/may/13/cruel-ethiopia/ [accessed May 12, 2010]. Interviews for this project and conversations with Ethiopian ex-patriots living in the United States are fully consistent with these published reports.

In addition to the CSO Law there has been recent anti-terrorism legislation and legislation directed at controlling the press. This legislation restricts public meetings and published expression of opinions and reports of the news. People also report sudden arrests that are perceived as ad hoc and arbitrary where due process protections of the courts are minimal. Hearing rumors that they will be arrested journalists we have met have fled the country. Few of the leading indigenous journalists remain working and even some international reporters have been arrested and either expelled or threatened with expulsion. Fear was palpable among several of those people interviewed for this project. People expressed concern that we were actually working for the secret police, that quotations would be attributed to them, or even that their organizations could be identified.

Thus, in the report that follows I will present information taken from interviews in a way that protects the confidentiality of interview respondents. We also will not give reference to U.S. Ethiopian residents who have provided detailed information in support of this report. Detailed field notes on each interview exist and are stored in a locked office at Bucknell University. Some information for this report is contained in academic papers presented at international research conferences and submitted for publication in academic journals. A diligent researcher could unearth these papers but they will not be cited in this report out of concern for the safety of Ethiopian collaborators for this project who continue to live in the country. Research procedures for this project were reviewed by the Bucknell University Institutional Review Board protecting the rights of human subjects during the 2008-2009 school year.

A Historical Role for NGOs and Civil Society Organizations

Legal changes and government enforcement represent radical societal changes in Ethiopia because NGOs have had an important presence in the country since the time of the famine in the 1970s and 1980s. There has been an important presence of international NGOs like Oxfam, Action Aid, Save the Children, Catholic Relief, and the Consortium of Religious Development Organizations. These actors began providing simple hunger relief, then moved to develop more sustainable programs that they term development and then they became involved in the government policy process.

Indigenous Ethiopian NGOs have worked in partnership with the international NGOs from the time of the 1970s forward, often providing impressive and effective programs and services. International and local NGOs were important supporters of the revolutionary movement against the brutal communist regime, the Dergue, that overthrew Haile Selasie in the late 1960s and continued until 1991. Evidence of the unwitting participation of the international relief community in the revolution was provided by a Spring 2010 BBC report. It detailed the way that significant amounts of funds generated by the Band Aid concerts organized by Bob Geldof, raising $100 million for relief organizations like Christian Aid and Oxfam, apparently were channeled into the feeding of troops and the purchase of arms by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) (cited in Epstein 2010; Martin Plaut, BBC: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p006dyn3 [accessed May 13, 2010]). Local observers suggest that this was not an isolated occurrence (academic papers).

Some interpreters suggest that because NGOs supported the revolution, the new government conformed to expectations that the new constitution, written between 1991 and 1994, would endorse concepts of democratic governance (this history is provided in our academic papers). The constitution guarantees freedom of association, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and it states that international human rights treaties signed by Ethiopia have the force of law. The CSO Law and the recent anti-terror and press laws specifically negate these constitutional provisions. Since several sections of the constitutions say they apply only if laws have not been passed that negate them, the new laws may not be unconstitutional (Human Rights Watch 2008).

Epstein (2010) reports that according to government sources ethnic divisions create a level of social and political volatility in Ethiopia and makes tight political control necessary. They say this is especially true heading into an election (scheduled for May 23, 2010). Political unrest followed the 2005 parliamentary elections. Critics tell us the unrest occurred because the opposition CUD party defeated the government overwhelmingly in Addis Ababa and produced a close vote elsewhere in the country. By denying the voting results and jailing opposition leaders, it is argued, the government provoked violence (Human Rights Watch 2010; Epstein 2010). Since election violations were never confirmed by outside observers, observers sympathetic to the government (including some of our interviewees) suggest that tight social and political controls are a prudent measure to prevent ethnic civil war.

After giving this ethnic division argument, Epstein goes on to offer evidence that Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has strong Stalinist and Marxist-Leninist leanings. She tells us of study groups he created on this theme in the 1980s. She suggests that while his government gave lip service to democratic principles and practices when it took power that this never was a serious point of commitment for him. Whether or not he truly is a Stalinist in terms of personal philosophy, interviewees including representatives of Western governments repeatedly used this term to describe the government. Perhaps a softer phrasing is to say that Ethiopia is following the “Chinese model of development.” The Chinese have an important presence in Ethiopia and they are especially apparent in the national road-building program.

What is broadly apparent is that the Ethiopian government is highly centralized, authoritarian in style, intolerant of political opposition, and willing to use arrest and intimidation without due process protections as a way of stifling opposition. The force of the detailed Human Rights Watch (2010) report is that membership in the ruling political party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), is required and party control is mandated in all civil jurisdictions down to the level of small political groups organized within kebelas—the village level of government. People are forced to participate in government programs including work programs, the report suggests, and if people refuse to join the party they may be denied food aid. In keeping with this control, free speech and political opposition groups usually are not tolerated.

In light of this level of repression it is puzzling that Western governments and charitable NGOs give more foreign aid to Ethiopia than to any other country in sub-Saharan Africa. One reason for this is that Ethiopia has great geo-political strategic importance since it is a large, Christian country surrounded by Islamic countries. Some of those Islamic countries like Somalia and Yemen have dangerous terrorist elements (McLure 2009).

Development vs. Civil Society Organizations

A different argument is that big Western aid programs are essentially a-political. Epstein (2010) suggests that they are following Jeffrey Sachs (2005) argument from The End of Poverty that investing heavily in a few locations would allow for eliminating all of the social and economic problems that cause structural reproduction of poverty.

Following this idea, administrators working in large Western financed aid programs give skeptical reports about political repression. Epstein (2010) quotes a World Bank official as saying that reports of political oppression are “anecdotal”. I heard the same comment from workers in other large aid programs.

The argument is that Human Rights Watch went to areas of Ethiopia where political opposition is most active and, not surprisingly, they encountered conflict and harsh treatment from the government. In areas where the EPRDF is strong citizens support government programs. This statement fits what I saw observing a program in Tigray where a massive irrigation program could only work if there was solidarity among residents and willingness to be restrained about cutting wood or overgrazing pastures.

On the other hand, food aid administrators may simply judge the kind of political control and repression reported by Human Rights Watch as outside of their jurisdiction. Within the development industry, civil society organizations that work on rights, democracy, and conflict resolution are perceived as fundamentally different from organizations that do humanitarian work and the massive programs run in Ethiopia to reduce food insecurity.

Reading evaluations of the Productive Safety Nets Program (PSNP) and the Other Food Security Program (OFSP) (Gilligan et al, 2008; Gilligan et al 2009) funded by USAID and the international donor group, one sees that questions about political oppression and equity are simply absent from the discussion. Perhaps this is appropriate since in these reports one also sees how desperately poor many Ethiopians are, especially in those parts of the country targeted for food relief and famine disaster assistance. Many families have incomes of less than $300 per year and meager fixed assets. With food cost inflation rates (partly caused by poor weather) ranging from 75.3% in Tigray to 186.7% in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR—a state in the southern part of Ethiopia) with income increasing at the rate of 93.8% in Tigray (keeping residents slightly ahead of inflation in terms of purchasing power) and 30.3% in Oromiya and 71.9% in SNNPR (where residents lost purchasing power) citizens are chronically and increasingly food insecure.

There is an argument that when people are this poor and so immediately threatened with starvation the first and primary question is how to help them to build family assets so that they can withstand food shocks (from disease or weather disasters). Massive aid programs in Ethiopia are centrally concerned with how to produce sustainable changes by expanding community resources, helping farmers to build assets so that they can work their way out of poverty, and protecting them from having to sell everything in disaster times in order to survive. Evidence-based program improvements and careful economic modeling are taken as the best means to improve life circumstances.

On the other hand, as Epstein (2010) argues, chronic hunger may have as much to do with restrictions on land ownership and rural-to-urban migration enforced by the government as it does with bad weather. Land reform instituted by the previous regime, the Dergue, has been retained and is a policy where farmers are given the right to use a plot of land but do not own it. This means that if they choose to leave an area seeking better economic opportunities they cannot sell their land and use the assets to relocate. It also means that over generations as land is subdivided among the children of a family plots of land become smaller and smaller. Family land plots in Tigray when I visited were about .35 hectares per families and estimates are that it takes at least .5 hectare to support a family. The best environmental and agricultural improvements will not eliminate hunger if families do not have enough land.

Furthermore, reading the Gilligan et al (2009) evaluation of the PSNP food program, one finds that some of the greatest impediments to program success are administrative. Families inconsistently receive food or cash distributions and when they put in labor on public works projects that is required by the PSNP program as an exchange for receiving food aid they often are not paid the resources that they earn. This makes it impossible for them to build up any assets and assets are essential if they are to buy food during famine periods.

Probably inefficiencies in local governance and administration play a significant role in failures to deliver promised resources to families. But improving local governance is what civil society organizations do. One also wonders whether failures to distribute aid might not come precisely from the political coercion and discrimination Human Rights Watch reports observing in the poorest communities.

Grass Roots Democracy

When President Obama (2010) listed Ethiopia with North Korea and Iran as among the countries most repressive with respect to press freedom you know there is a problem. It is impressive to read the testimony by Human Rights Watch about the generally coercive and repressive conditions in the country. There is not much doubt that there were electoral abuses after the 2005 Parliamentary elections and the government seems intent on making sure there is no meaningful opposition when the 2010 Parliamentary elections takes place on May 23, 2010. Implementation of the Charities and Societies Law seems timed, in part, to make sure that civil society organizations that played an important role in mobilizing the electorate in 2005 will not be able to play a meaningful role in the current elections.

It is disturbing that the government would introduce a structural change in the status of charities and societies if the intention is simply to control an election. Some of our informants interpreted the law in this way and predicted that the government would become more relaxed about enforcing provisions of the law after the election takes place.

Indeed, this is a pattern we have seen in other countries when civil society organizations became strongly organized and play an influential role in electoral politics. Moynihan (1969) talks about reprisals by the political system against community based organizations as the reason the War on Poverty was ended in the U.S. Nick Acheson and I saw a similar reaction in Northern Ireland in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement (Acheson and Milofsky 2008). Howell and colleagues also document a backlash against civil society organizations in many countries in the wake of the “War on Terror” (Howell, et al 2008; Howell et al 2010). There is an argument that “representative democracy” trumps “grass roots democracy.” Civil society organizations play important roles in certain phases of national development but when those phases end the politicians often act aggressively to push civil society actors out of participatory processes related to government.

We will examine this idea in the next section of this blog where I will tell about informants’ experiences as state builders. Civil society organizations in Ethiopia helped to fill an institutional vacuum in the fifteen-year period after the new state was formed. Perhaps the state has now reached a level of institutional development that the sort of informal participation represented by civil society organizations in the processes of governance is no longer needed.

While there certainly is validity to this argument it also is true that the Ethiopian government is repressive in the extreme. Counter to the institutionalization argument is the argument that a Stalinist government is just now becoming confident about its control of the country and its ability to flaunt the power of the United States and other Western governments and institutions. In this view we are not seeing a temporary crackdown and an attempt to assert the power of elected politicians over grass roots activists. We are seeing emergence of a system that makes it impossible for a political opposition to emerge, gain standing, and compete in elections. Furthermore, the dominant political party and the government with its military intrude into every avenue of society including the humanitarian system for providing food relief.

Eliminating so-called “advocacy” activities through the CSO law is central to this repressive process. This is the reason that outside organizations like ARNOVA should object.

Bibliography

Acheson, N, and C. Milofsky (2008). “Peace Building and Participation in Northern Ireland: Local Social Movements and the Policy Process since the ‘Good Friday’ Agreement.” Ethnopolitics 7 (1): 63-80.

Epstein, Helen (2010) “Cruel Ethiopia.” May 13. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/may/13/cruel-ethiopia/ (accessed May 12, 2010)

FONDACA (2006). European Charter of Active Citizenship. http://www.fondaca.org/file/Archivio/Documenti/EuropeanCharterofActiveCitizenship_FINAL.pdf

Gerima, Haile (2008). Teza [http://www.tezathemovie.com/].)

Gilligan, D.O., J. Hoddinott, N.R. Kumar, and A. S. Taffesse (December 2008) The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme and its LinkagesWashington, DC: International Food Policy Institute. http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ifpridp00839.pdf

Gilligan, D.O., J. Hoddinott, N.R. Kumar, and A. S. Taffesse (June 30, 2009). “An Impact Evaluation of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Nets Program.” Washington, DC: International Food Policy Institute.

Howell, J. and J. Lind (2010). “Securing the World and Challenging Civil Society: Before and After the ‘War on Terror.’” Development and Change, 41 (2): 279-291. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27859/ [accessed May 15, 2010].

Howell, J.; A. Ishkanian; E. Obadare; and H. Seckinelgin (2008). “The Backlash Against Civil Society in the Wake of the Long War on Terror.” Development in Practice. 18 (1): 82-93. Abstract at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/3731/ [accessed May 15, 2010].

Human Rights Watch (Oct. 13, 2008). Analysis of Ethiopia’s Draft Civil Society Law. http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/10/13/analysis-ethiopia-s-draft-civil-society-law-0 (accessed May 12, 2010)

Human Rights Watch (March 24, 2010), One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure. Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Ethiopia.

Lazaro, Fred De Sam (2010). “Ethiopia’s Abundent Farming Investments Leave Many Still Hungry.” PBS Reports, April 22. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/social_issues/jan-june10/ethiopia_04-22.html [accessed May 14, 2010].

McLure, Jason (2009). “The Troubled Horn of Africa. Can the War-Torn Region Be Stabilized?” CQ Global Researcher 3(6): 149-176. June.

McLure, Jason (2010). “Ethiopian Rights Groups Forced to Reduce Work Before Elections.” Bloomberg News, Friday, May 14. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-14/ethiopian-rights-groups-forced-to-reduce-work-before-elections.html [accessed May 14, 2010].

Obama, Barack (2010). “Statement by the President on World Press Freedom Day.” Washington, DC: The White House. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/statement-president-world-press-freedom-day

Plaut, Martin (2010). “Aid for Arms in Ethiopia.” BBC World Service, Assignment. March 7. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p006dyn3 [accessed May 13, 2010].

Sachs, Jeffrey (2005). The End of Poverty. Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: The Penguin Group.

Sen, Amartya (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

This blog presents a report on the impact of Ethiopia’s Charities and Societies Law on civil society organizations and indigenous people who lead these organizations and who do NGO-related research. I have family members and friends who live in or have fled Ethiopia and over the last three years I have heard many stories about arrests, intimidations, and organizational closings. These actions have cut off what had been a fifteen-year tradition of building civil society organizations and using them to address desperate poverty and to build democracy in this country.

Ethiopia is the second most populous country in Africa with about 90 million people. It occupies a land area one-third the size of the United States. It also is one of the poorest countries and food insecurity is a chronic problem there.

I spent two weeks in Ethiopia during April 2010 and most of my time was occupied interviewing NGO leaders and visiting development projects in the countryside. I presented myself in these interviews as a board member of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organization and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA). As a board member I think we ought to support the principle that citizens all over the world should have basic rights to freedom of speech and association.

Furthermore, within the framework of certain principles of operation, nonprofit organizations (as we call them in the United States) should be protected from governmental interference and that their leaders should have due process protections. I have worked with the Italian Active Citizens Network for several years and have been aware of their effort to create a standard legal code defining the rights of nonprofit organizations in all EU states (FONDACA, 2006). I do not believe that this code has been passed by the EU.

The FONDACA code, worked out in collaboration with similar citizens organizations from across Europe, began with the recognition that some countries in the EU have restrictive laws concerning what it calls “active citizenship organizations (ACO)” because their legal traditions have not recognized rights to free association. As with other domains of legal and economic life in Europe, the FONDACA group argued that a uniform code is needed. Basic principles are that ACOs should be treated as autonomous firms and as firms they should have their autonomy legally protected. Furthermore, ACO members should have their rights to associate freely and to engage in free speech on public issues where their actions are not politically partisan, violent, or dangerous.

My thought is that ARNOVA ought to endorse the FONDACA charter and support the principle that nonprofit and civil society organizations should be guaranteed certain freedoms. Furthermore, as an organization we should give expressions of concern when those rights are abused. We ought to reach out to national nonprofit associations in countries that are affected and we also should invite nonprofit scholars (some of whom I met in Ethiopia) to participate. We should communicate with international charities and governments that continue to provide aid and support in countries where civil society rights are abused. We also should, as researchers, teachers, and activists, teach about civil society principles and abuses that occur around the world.

My investigations in Ethiopia were meant to explore how a restrictive NGO law is implemented in practice. Do civil society organizations retain their rights as autonomous firms? Are rights defined and protected in terms of free association, free speech, and nonpartisan voter education and mobilization? If there is a problem my intention is to convince ARNOVA to pass policies that endorse political freedom for those involved in nonprofit organizations around the world.

The Charities and Societies Law

In January of 2009 the Ethiopian Parliament passed the Charities and Societies Proclamation and after a one-year grace period this legislation known as the CSO Law began to be fully enforced by a new organization referred to as the Agency. The law distinguishes between charities, organizations that generally fall into categories defined by U.S. law as 501(c)(3) organizations, and societies, which are member benefit organizations.

The Law further distinguishes between organizations based on their sources of funding. Those that receive 90% or more of their funds from Ethiopian citizens are called “local” organizations. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) based in Ethiopia but that receive more than 10% of their funding from international sources (including citizens living overseas who donate funds back to organizations in their homeland) are termed “resident” organizations. Organizations based outside of the country and funded outside are called “international” organizations. Religious organizations are not affected by the Law nor are international charities that are registered with the government nor community-level, indigenous savings societies called “edir” or “equb”.

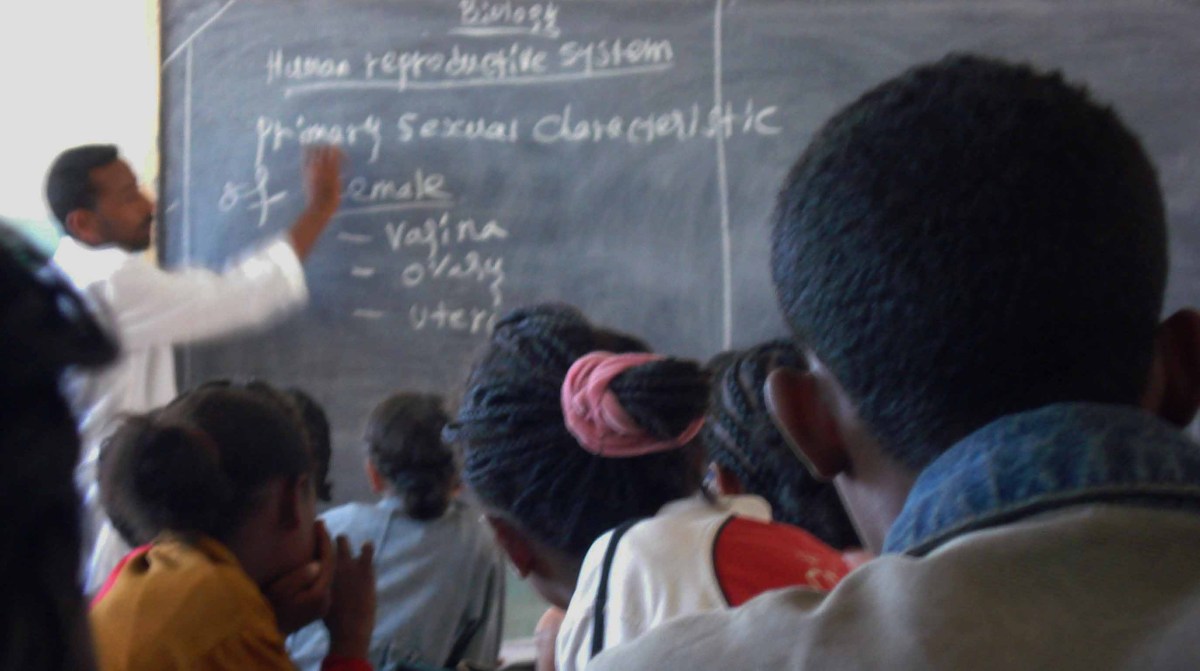

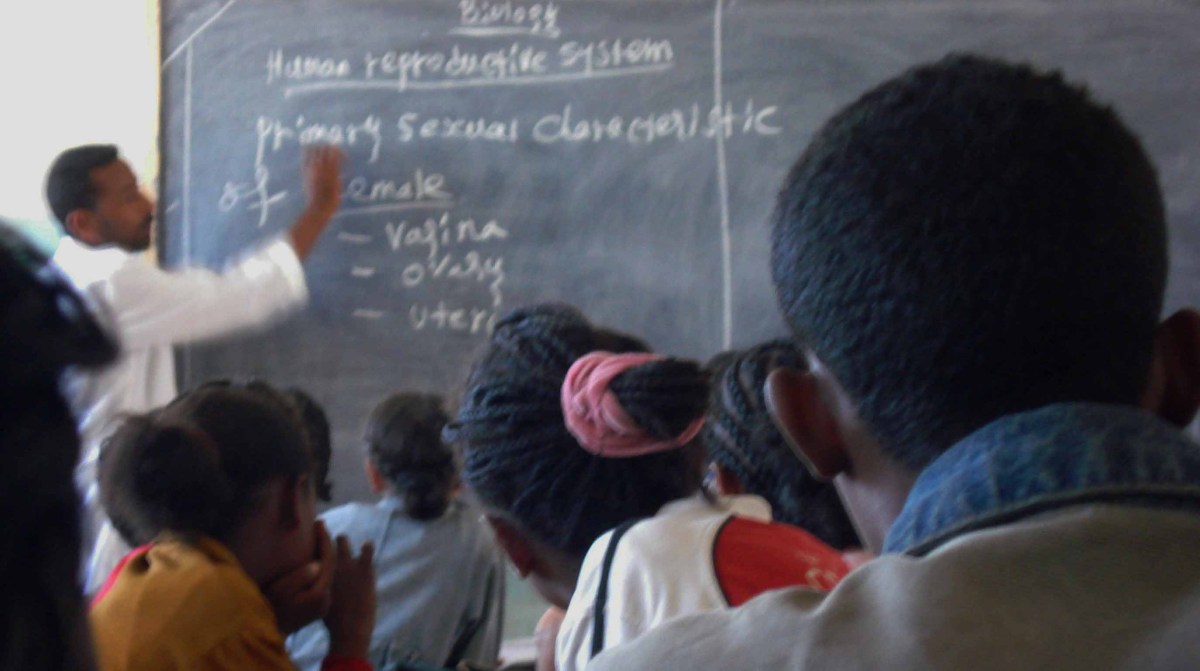

The charitable purposes that define the category of charities are organizations that: (a) work to prevent or alleviate poverty or disaster; (b) seek advancement of the economy and social development and environmental protection or improvement; (c) advancement of animal welfare; (d) advancement of education; (e) advancement of health or the saving of lives; (f) the advancement of the arts, culture, heritage or science; (g) advancement of amateur sport and the welfare of youth; (h) relief of those in need by reason of age, disability, financial hardship, or other disadvantage; (i) advancement of capacity building on the basis of the country’s long-term development directions; (j) the advancement of human and democratic rights; (k) the promotion of equality of nations, nationalities, and that of gender and religion; (l) the promotion of the rights of the disabled and children’s rights; (m) the promotion of conflict resolution or reconciliation; (n) promotion of the efficiency of the justice and law enforcement services; and (o) any other purposes as may be prescribed by directives of the agency.

Advocacy

Among these, only local Ethiopian charities and societies (those receiving less than 10% of their resources from other countries) can work on activities that fall in categories (j) through (n).

These activities are considered “advocacy” activities. The rationale of this legislation is “to ensure that nongovernmental organizations are ‘Ethiopian in character’, not to cut their funding, said Atakilti Gidey, deputy director general of the country’s Charities and Societies Agency.”

“’If you provide a huge amount of money in this area and that money comes from outside, their work will not be for the government and the people, it will be for foreigners,’ he said in an interview in Addis Ababa on May 12.” (McLure, Jason 2010).

Advocacy activities are distinguished from development or capacity building activities, which continue to be allowed. Three important areas of advocacy that have been ended for resident organizations are nonpartisan voter education including the organization of public forums about public issues and the performance of government, conflict resolution work, especially involving sustained disputes between ethnic groups or between critical social movements and the state, and work fostering development of rights, including the rights of women, children, and the disabled.

There is face validity to the government’s argument that wealthy international NGOs should not be conceiving and funding programs that advance their Western values rather than Ethiopian values. Our respondents complained, however, that the programs their organizations ran were created by Ethiopians and sold to outside funders rather than being responses to outside funding opportunities. The programs worked because they were locally adapted to the community practices and cultural values that prevail in Ethiopian communities.

My informants argued that the government has no test to distinguish an “Ethiopian” value from a Western value in the context of a program that develops women’s rights or that seeks to mediate a land boundary dispute between two ethnic groups. Furthermore, the government did not develop its regulations based on specific complaints about programs. Rather, the government sought change because when citizens learn about basic rights they begin to become interested in public issues and start to exercise the rights of free speech and free association. These rights might be seen as Western values. The counter view expressed by Nobel Prize winning Economist Amartya Sen (1999) is that basic freedoms are universal human values and that they are necessary for the creative and entrepreneurial action that is necessary for development to occur.

Restrictions

Since historically there has been no practice of fundraising for impersonal organizations or abstract causes the new regulation has abruptly ended the activities of many important and effective civil society organizations. By one estimate the number of CSOs has been reduced form about 4600 to about 1400 in a period of three months in early 2010. Staff members have been reduced by 90% or more among many of those organizations that survive according to my informants (McLure 2010).

The CSO Law includes a variety of administrative controls that are to be administered by the Charities and Societies Agency. The implication is that NGOs are an extension of the state rather than private, autonomous firms. Yet the organizations are expected to raise their own resources, make their own program choices, recruit volunteers on their own, and be accountable to outside funding sources.

Among the administrative controls included in the Law, organizations may not spend more than 30% of their annual budgets on administrative expenses. They are required to produce an annual report and an audited accounting report. While these fit with standards of good practice in U.S. nonprofits the difference is that in Ethiopia the government is mandated to scrutinize the records of nonprofits and violations can be met with large fines or even imprisonment. This kind of monitoring would be extremely difficult for government to carry out in the U.S. and thus these regulations are not likely to be systematically enforced. Rather, the administrative controls give government the right to use these regulations to attack organizations they dislike. Furthermore, representatives of the Agency have the right to attend administrative meetings and to mandate changes in procedure based on the judgment of the representative. There is no mechanism for appeal. Nor do procedures guaranteeing due process exist for agencies to depend upon.

One respondent pointed out that he is personally held accountable to funders for the operations of his agency. Since his organization periodically undertakes large construction projects that require a year or more of planning he simply cannot meet the requirement that less than 30% of resources be spent on administrative expenses. His funder holds him to tight standards of accountability. Adherence to these controls could become impossible for him if agency representatives were to impose administrative changes that may or may not take his operating requirements into account. This individual also has encountered repeated demands for bribes and without a powerful funder behind him is sure that he would have ended up in prison for resisting those demands. This individual chose to close his NGO rather than try to live with the constraints imposed by the law. Although Epstein (2010) tells us that Ethiopia is not particularly corrupt compared to other countries Transparency International (2009) tells us that Ethiopia ranks 120th out of 18o countries in terms of citizens’ perceptions of corruption.

Political Coercion

As McLure and others note, many observers view the CSO Law as one part of a broad-based effort by the government to eliminate public discussion of issues, to destroy opposition political parties, and to remove decentralized associations and service providers in favor of an authoritarian, centralized, hierarchical state. Important testimony and analysis is provided by the UK-based NGO, Human Rights Watch that provided an analysis of the proposed law in 2008 (Human Rights Watch Oct. 13, 2008). That report found many parallels between the Ethiopian law and one passed in Zimbabwe in 2006. The Zimbabwe law led to widespread international condemnation.

Human Rights Watch recently followed with a long and detailed report based on over 200 interviews throughout the country. This spring 2010 report documents political abuses, restrictions of freedom, and systematic elimination of the social structure that supports civil society (Human Rights Watch, March 24, 2010), One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure. Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Ethiopia. Another recent, powerful analysis, based on first-person observations and interviews, is provided by Helen Epstein in the May 13, 2010, issue of The New York

Review of Books Epstein, Helen (May 13, 2010) “Cruel Ethiopia.” Interviews for this project and conversations with Ethiopian ex-patriots living in the United States are fully consistent with these published reports.

In addition to the CSO Law there has been recent anti-terrorism legislation and legislation directed at controlling the press. This legislation restricts public meetings and published expression of opinions and reports of the news. People also report sudden arrests that are perceived as ad hoc and arbitrary where due process protections of the courts are minimal. Hearing rumors that they will be arrested journalists we have met have fled the country. Few of the leading indigenous journalists remain working and even some international reporters have been arrested and either expelled or threatened with expulsion. Fear was palpable among several of those people interviewed for this project. People expressed concern that we were actually working for the secret police, that quotations would be attributed to them, or even that their organizations could be identified.

Thus, in the report that follows I will present information taken from interviews in a way that protects the confidentiality of interview respondents. We also will not give reference to U.S. Ethiopian residents who have provided detailed information in support of this report. Detailed field notes on each interview exist and are stored in a locked office at Bucknell University. Some information for this report is contained in academic papers presented at international research conferences and submitted for publication in academic journals. A diligent researcher could unearth these papers but they will not be cited in this report out of concern for the safety of Ethiopian collaborators for this project who continue to live in the country. Research procedures for this project were reviewed by the Bucknell University Institutional Review Board protecting the rights of human subjects during the 2008-2009 school year and re-approved in 2010.

A Historical Role for NGOs and Civil Society Organizations

Legal changes and government enforcement represent radical societal changes in Ethiopia because NGOs have had an important presence in the country since the time of the famine in the 1970s and 1980s. There has been an important presence of international NGOs like Oxfam, Action Aid, Save the Children, Catholic Relief, and the Consortium of Religious Development Organizations. These actors began providing simple hunger relief, then moved to develop more sustainable programs that they term development and then they became involved in the government policy process.

Indigenous Ethiopian NGOs have worked in partnership with the international NGOs from the time of the 1970s forward, often providing impressive and effective programs and services. International and local NGOs were important supporters of the rebellion against the brutal communist regime, the Dergue, that overthrew Haile Selasie in the late 1960s and continued until 1991. Evidence of the unwitting participation of the international relief community in the rebellion was provided by a Spring 2010 BBC report. It detailed the way that significant amounts of funds generated by the Band Aid concerts organized by Bob Geldof, raising $100 million for relief organizations like Christian Aid and Oxfam, apparently were channeled into the feeding of troops and the purchase of arms by the Tigrayan People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) (cited in Epstein 2010). Local observers suggest that this was not an isolated occurrence (academic papers).

Some interpreters suggest that because NGOs supported the rebellion the government was especially inclined to incorporate democratic principles as it built the new government. It was as though the government recognized that NGOs could support groups opposed to the government since it had prospered with that support. The new government conformed to expectations that the new constitution, written between 1991 and 1994, would endorse concepts of democratic governance (this history is provided in our academic papers). The constitution guarantees freedom of association, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and it states that international human rights treaties signed by Ethiopia have the force of law.

The CSO Law and the recent anti-terror and press laws specifically negate these constitutional provisions. Since several sections of the constitutions say they apply only if laws have not been passed that negate them, the new laws may not be unconstitutional (Human Rights Watch 2008).

Epstein (2010) reports that according to government sources ethnic divisions create a level of social and political volatility in Ethiopia and makes tight political control necessary. They say this is especially true heading into an election (scheduled for May 23, 2010). Political unrest followed the 2005 parliamentary elections. Critics tell us the unrest occurred because the opposition CUD party defeated the government overwhelmingly in Addis Ababa and produced a close vote elsewhere in the country. By denying the voting results and jailing opposition leaders, it is argued, the government provoked violence (Human Rights Watch 2010; Epstein 2010). Some people I talked to said election violations were never confirmed by outside sources. This is not correct since both the Carter Center (2005) and the European Union Election Observation Mission (2005) issued reports confirming that serious post-election abuses occurred. Nonetheless, observers sympathetic to the government (including some of our interviewees) suggest that tight social and political controls are a prudent measure to prevent ethnic civil war.

After giving this ethnic division argument, Epstein goes on to offer evidence that Prime Minister Meles Zenawi has strong Stalinist and Marxist-Leninist leanings. She tells us of study groups he created on this theme in the 1980s. She suggests that while his government gave lip service to democratic principles and practices when it took power that this never was a serious point of commitment for him. Whether or not he truly is a Stalinist in terms of personal philosophy, interviewees including representatives of Western governments repeatedly used this term to describe the government. Perhaps a softer phrasing is to say that Ethiopia is following the “Chinese model of development.” The Chinese have an important presence in Ethiopia and they are especially apparent in the national road-building program.

What is broadly apparent is that the Ethiopian government is highly centralized, authoritarian in style, intolerant of political opposition, and willing to use arrest and intimidation without due process protections as a way of stifling opposition. The force of the detailed Human Rights Watch (2010) report is that membership in the ruling political party, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), is required and party control is mandated in all civil jurisdictions down to the level of small political groups organized within kebelas—the village level of government. People are forced to participate in government programs including work programs, the report suggests, and if people refuse to join the party they may be denied food aid. In keeping with this control, free speech and political opposition groups usually are not tolerated.

In light of this level of repression it is puzzling that Western governments and charitable NGOs give more foreign aid to Ethiopia than to any other country in sub-Saharan Africa. One reason for this is that Ethiopia has great geo-political strategic importance since it is a large, Christian country surrounded by Islamic countries. Some of those Islamic countries like Somalia and Yemen have dangerous terrorist elements (McLure 2009).

Development vs. Civil Society Organizations

A different argument is that big Western aid programs are essentially a-political. Epstein (2010) suggests that they are following Jeffrey Sachs (2005) argument from The End of Poverty that investing heavily in a few locations would allow for eliminating all of the social and economic problems that cause structural reproduction of poverty.

Following this idea, administrators working in large Western financed aid programs give skeptical reports about political repression. Epstein (2010) quotes a World Bank official as saying that reports of political oppression are “anecdotal”. I heard the same comment from workers in other large aid programs.

The argument is that Human Rights Watch went to areas of Ethiopia where political opposition is most active and, not surprisingly, they encountered conflict and harsh treatment from the government. In areas where the EPRDF is strong citizens support government programs. This statement fits what I saw observing a program in Tigray where a massive irrigation program could only work if there was solidarity among residents and willingness to be restrained about cutting wood or overgrazing pastures.

On the other hand, food aid administrators may simply judge the kind of political control and repression reported by Human Rights Watch as outside of their jurisdiction. Within the development industry, civil society organizations that work on rights, democracy, and conflict resolution are perceived as fundamentally different from organizations that do humanitarian work and the massive programs run in Ethiopia to reduce food insecurity.

Reading evaluations of the Productive Safety Nets Program (PSNP) and the Other Food Security Program (OFSP) (Gilligan et al, 2008; Gilligan et al 2009) funded by USAID and the international donor group, one sees that questions about political oppression and equity are simply absent from the discussion. Perhaps this is appropriate since in these reports one also sees how desperately poor many Ethiopians are, especially in those parts of the country targeted for food relief and famine disaster assistance. Many families have incomes of less than $300 per year and meager fixed assets. With food cost inflation rates (partly caused by poor weather) ranging from 75.3% in Tigray to 186.7% in the Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples Region (SNNPR—a state in the southern part of Ethiopia) with income increasing at the rate of 93.8% in Tigray (keeping residents slightly ahead of inflation in terms of purchasing power) and 30.3% in Oromiya and 71.9% in SNNPR (where residents lost purchasing power) citizens are chronically and increasingly food insecure.

There is an argument that when people are this poor and so immediately threatened with starvation the first and primary question is how to help them to build family assets so that they can withstand food shocks (from disease or weather disasters). Massive aid programs in Ethiopia are centrally concerned with how to produce sustainable changes by expanding community resources, helping farmers to build assets so that they can work their way out of poverty, and protecting them from having to sell everything in disaster times in order to survive. Evidence-based program improvements and careful economic modeling are taken as the best means to improve life circumstances.

On the other hand, as Epstein (2010) argues, chronic hunger may have as much to do with restrictions on land ownership and rural-to-urban migration enforced by the government as it does with bad weather. Land reform instituted by the previous regime, the Dergue, has been retained and is a policy where farmers are given the right to use a plot of land but do not own it. This means that if they choose to leave an area seeking better economic opportunities they cannot sell their land and use the assets to relocate. It also means that over generations as land is subdivided among the children of a family plots of land become smaller and smaller. Family land plots in Tigray when I visited were about .35 hectares per families and estimates are that it takes at least .5 hectare to support a family. The best environmental and agricultural improvements will not eliminate hunger if families do not have enough land.

Furthermore, reading the Gilligan et al (2009) evaluation of the PSNP food program, one finds that some of the greatest impediments to program success are administrative. Families inconsistently receive food or cash distributions and when they put in labor on public works projects that is required by the PSNP program as an exchange for receiving food aid they often are not paid the resources that they earn. This makes it impossible for them to build up any assets and assets are essential if they are to buy food during famine periods.

Probably inefficiencies in local governance and administration play a significant role in failures to deliver promised resources to families. But improving local governance is what civil society organizations do. One also wonders whether failures to distribute aid might not come precisely from the political coercion and discrimination Human Rights Watch reports observing in the poorest communities.

Grass Roots Democracy

When President Obama (2010) listed Ethiopia with North Korea and Iran as among the countries most repressive with respect to press freedom you know there is a problem. It is impressive to read the testimony by Human Rights Watch about the generally coercive and repressive conditions in the country. There is not much doubt that there were electoral abuses after the 2005 Parliamentary elections and the government seems intent on making sure there is no meaningful opposition when the 2010 Parliamentary elections takes place on May 23, 2010. Implementation of the Charities and Societies Law seems timed, in part, to make sure that civil society organizations that played an important role in mobilizing the electorate in 2005 will not be able to play a meaningful role in the current elections.

It is disturbing that the government would introduce a structural change in the status of charities and societies if the intention is simply to control an election. Some of our informants interpreted the law in this way and predicted that the government would become more relaxed about enforcing provisions of the law after the election takes place.

Indeed, this is a pattern we have seen in other countries when civil society organizations became strongly organized and play an influential role in electoral politics. Moynihan (1969) talks about reprisals by the political system against community based organizations as the reason the War on Poverty was ended in the U.S. Nick Acheson and I saw a similar reaction in Northern Ireland in the wake of the Good Friday Agreement (Acheson and Milofsky 2008). Howell and colleagues also document a backlash against civil society organizations in many countries in the wake of the “War on Terror” (Howell, et al 2008; Howell et al 2010). There is an argument that “representative democracy” trumps “grass roots democracy.” Civil society organizations play important roles in certain phases of national development but when those phases end the politicians often act aggressively to push civil society actors out of participatory processes related to government.

We will examine this idea in the next section of this blog where I will tell about informants’ experiences as state builders. Civil society organizations in Ethiopia helped to fill an institutional vacuum in the fifteen-year period after the new state was formed. Perhaps the state has now reached a level of institutional development that the sort of informal participation represented by civil society organizations in the processes of governance is no longer needed.

While there certainly is validity to this argument it also is true that the Ethiopian government is repressive in the extreme. Counter to the institutionalization argument is the argument that a Stalinist government is just now becoming confident about its control of the country and its ability to flaunt the power of the United States and other Western governments and institutions. In this view we are not seeing a temporary crackdown and an attempt to assert the power of elected politicians over grass roots activists. We are seeing emergence of a system that makes it impossible for a political opposition to emerge, gain standing, and compete in elections. Furthermore, the dominant political party and the government with its military intrude into every avenue of society including the humanitarian system for providing food relief.

Eliminating so-called “advocacy” activities through the CSO law is central to this repressive process. This is the reason that outside organizations like ARNOVA should object.

References

Acheson, N, and C. Milofsky (2008). “Peace Building and Participation in Northern Ireland: Local Social Movements and the Policy Process since the ‘Good Friday’ Agreement.” Ethnopolitics 7 (1): 63-80.

Carter Center (2005). Final Statement on the Carter Center Observation of the Ethiopia 2005 National Elections. (Septemhber). http://www.cartercenter.org/documents/2199.pdf [accessed May 18, 2010].

Epstein, Helen (2010) “Cruel Ethiopia.” May 13. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/may/13/cruel-ethiopia/ (accessed May 12, 2010)

Ethiopian Government (2009). “The Truth about Suspended CSOs”. Addis Ababa: A Week in the Horn, July 31, 2009. http://www.mfa.gov.et/Press_Section/Week_Horn_Africa_July_31_2009.htm

European Union Election Observation Mission (2005). Ethiopia Legislative Elections 2005 Final Report. http://ec.europa.eu/external_relations/human_rights/election_observation/ethiopia/final_report_en.pdf [accessed May 18, 2010]

FONDACA (2006). European Charter of Active Citizenship. http://www.fondaca.org/file/Archivio/Documenti/EuropeanCharterofActiveCitizenship_FINAL.pdf

Gerima, Haile (2008). Teza [http://www.tezathemovie.com/].)

Gilligan, D.O., J. Hoddinott, N.R. Kumar, and A. S. Taffesse (December 2008) The Impact of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Net Programme and its LinkagesWashington, DC: International Food Policy Institute. http://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/publications/ifpridp00839.pdf

Gilligan, D.O., J. Hoddinott, N.R. Kumar, and A. S. Taffesse (June 30, 2009). “An Impact Evaluation of Ethiopia’s Productive Safety Nets Program.” Washington, DC: International Food Policy Institute.

Hodinott, J.; S. Dercon; and P. Krishnan (2005). “Networks and Informal Mutual Support in 15 Ethiopian Villages.” Washington, DC: Food Policy Institute, 2005.

Howell, J. and J. Lind (2010). “Securing the World and Challenging Civil Society: Before and After the ‘War on Terror.’” Development and Change, 41 (2): 279-291. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/27859/ [accessed May 15, 2010].

Howell, J.; A. Ishkanian; E. Obadare; and H. Seckinelgin (2008). “The Backlash Against Civil Society in the Wake of the Long War on Terror.” Development in Practice. 18 (1): 82-93. Abstract at http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/3731/ [accessed May 15, 2010].

Human Rights Watch (Oct. 13, 2008). Analysis of Ethiopia’s Draft Civil Society Law. http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/10/13/analysis-ethiopia-s-draft-civil-society-law-0 (accessed May 12, 2010)

Human Rights Watch (March 24, 2010), One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure. Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Ethiopia. http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/03/24/one-hundred-ways-putting-pressure

Lazaro, Fred De Sam (2010). “Wells in Ethiopia Draw on Community Support.” PBS Reports. March 18. http://www.pulitzercenter.org/openitem.cfm?id=2267 [accessed May 14, 2010]

Lazaro, Fred De Sam (2010). “Ethiopia’s Abundent Farming Investments Leave Many Still Hungry.” PBS Reports, April 22. Special correspondent Fred de Sam Lazaro reports. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/social_issues/jan-june10/ethiopia_04-22.html [accessed May 14, 2010].

McLure, Jason (2009). “The Troubled Horn of Africa. Can the War-Torn Region Be Stabilized?” CQ Global Researcher 3(6): 149-176. June.

McLure, Jason (2010). “Ethiopian Rights Groups Forced to Reduce Work Before Elections.” Bloomberg News, Friday, May 14. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-14/ethiopian-rights-groups-forced-to-reduce-work-before-elections.html [accessed May 14, 2010].

Moynihan, Daniel P. (1969). Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding. New York: Free Press.

Obama, Barack (2010). “Statement by the President on World Press Freedom Day.” Washington, DC: The White House. http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/statement-president-world-press-freedom-day

Plaut, Martin (2010). “Aid for Arms in Ethiopia.” BBC World Service, Assignment. March 7. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p006dyn3 [accessed May 13, 2010].

Sachs, Jeffrey (2005). The End of Poverty. Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: The Penguin Group.

Sen, Amartya (1999). Development as Freedom. New York: Knopf.

Transparency International (2010). “Corruption Perceptions Index, 2009.” http://www.transparency.org/policy_research/surveys_indices/cpi/2009/cpi_2009_table [accessed May 19, 2010]

Civil Society in Ethiopia

I recently returned from Ethiopia where I spent my time interviewing NGO leaders with the help of a local reporter. I’ve been to Ethiopia a few times because my daughter lives there with her husband and son. Their work involves them in the world of journalism and NGO relief programs. I also have a colleague who is an exiled political leader so the escalating repression of the press and of civil society organizations has been one of our frequent topics of conversation.

There is an election for the parliament set to take place on May 23 and in the last month two very critical reports have appeared on civil society freedoms in Ethiopia. One is by Human Rights Watch and you can find it at:

Human Rights Watch (March 24, 2010), One Hundred Ways of Putting Pressure. Violations of Freedom of Expression and Association in Ethiopia. http://www.hrw.org/en/reports/2010/03/24/one-hundred-ways-putting-pressure

The other is by Helen Epstein and you can find it at: Epstein, Helen (2010) “Cruel Ethiopia.” May 13. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/may/13/cruel-ethiopia/ (accessed May 12, 2010)

I’d also note that Obama included Ethiopia on his list of countries most repressive towards the press (with North Korea and Iran).

I’d heard extreme reports about restrictions on civil liberties and the freedom of association in Ethiopia, often explained as part of the government’s effort to stamp out political opposition leading up to next week’s election. I wanted to learn for myself what was going on. One reason for my interest is that I am a board member of the Association for Research on Nonprofit Organizations and Voluntary Action (ARNOVA) and it seems to me our organization ought to concerned when the civil society sector of a large country (second most populous in Africa with 93 million people) is dramatically restricted. Another reason for concern is that Ethiopia receives more foreign aid than any other country in sub-Saharan Africa. The government was routinely described to me as a Stalinist military dictatorship. Is there a problem that the U.S. government supports this repressive state hoping to thwart terrorism and also to hold off starvation among millions of people (U.S. food aid feeds 7 million people)?

My task of the next few days is to write a report on my interviews with NGO leaders and to give an interpretation of what I learned. This will not be easy to write because I believe western academics mostly expect African governments to be inefficient, corrupt, and authoritarian. People are likely to ask why Ethiopia is different from anywhere else and whether it really is our place to challenge every state that does not do things “our” way (that might be the American way or the UK way or the Swedish way).

In fact, I believe that the Ethiopian government has less graft than many African governments. (Helen Epstein testifies to this although one our NGO leaders complained that petty extortion by government is constant and always puts a leader like him in danger of being put in jail.) Also, it is striking as you travel around Ethiopia how many large public works projects are going on (including public schooling in the smallest, most remote towns). I’ve heard it said that Ethiopia follows a plan of what they call “Chinese Development”. You can imagine what this means. Authoritarian repression of speech and association but lots of roads, dams, and schools.

Helen Epstein’s article follows this line of analysis and then makes a devastating case about the inhumane application of humanitarian relief. Despite massive food aid and dramatic agricultural programs people continue to starve because (a) under land reform families are not given large enough plots of land to farm to support a framily (.35 hectare per family in Tigray where I visited) and (b) because according to the Human Rights watch report the ruling political party (the EPRDF) controls government services at the smallest local jurisdiction level and will not give basic aid unless families join the party (which some refuse to do).

It’s a complex story.

I’d love to see comments about why I (or we) should be concerned about the human rights situation in Ethiopia. I suppose as I move along in my spring writing project I’ll post more here.